Chapter 2 Model Development Process

When used in the context of complex management decisions with many partners, environmental and ecological modeling often benefit from approaches that emphasize transparency, increase user input during development, and clearly communicated model assumptions and limitations (Van den Belt 2004; Voinov and Bousquet 2010; Herman et al. 2019). Here, a general five-step modeling process is followed that applies best practices in ecological model development (Grant and Swannack 2008). First, general relationships among essential ecosystem components are formally conceptualized to tell the story of “how the system works” (Fischenich 2008). Second, the model is quantified using a formal structure of functional relationships, algorithms, parameters, and numerical code. Third, models are evaluated relative to underlying scientific theory, numerical accuracy, and usability, which often entails techniques such as code checking, testing, verification, and sensitivity analyses. Fourth, a model is applied to a given management question, scenario, or assessment. Fifth, a strategy is developed and executed to communicate model development and application to technical and non-technical audiences. This process has been applied numerous times to select, adapt, or develop ecological models for USACE and non-USACE studies (e.g., S. Kyle McKay, Richards, and Swannack 2019; Herman et al. 2019), and the framework is intended to draw heavily from existing knowledge, data, and tools.

USACE policy (USACE 2011) defines a model as “a representation of a system for a purpose,” and thus specifying a modeling purpose and objective is often a foundational step in the modeling process. Here, our modeling objective is to articulate the mechanisms and magnitude of environmental effects of proposed coastal storm risk management actions in the New York Bight Ecosystem. However, this model (like all models) is being developed in a constrained environment with limited time and resources. Three key issues constrained and guided NYBEM development, each of which is addressed in subsequent sections:

The model domain is limited to the spatial extent of the focal USACE studies.

Model development is phased to align with USACE project planning milestones.

Transparency in model development and input from stakeholders and partners were actively embraced to increase the adoption and acceptance of the tools, given the high-profile nature of the studies.

2.1 Spatial Extent

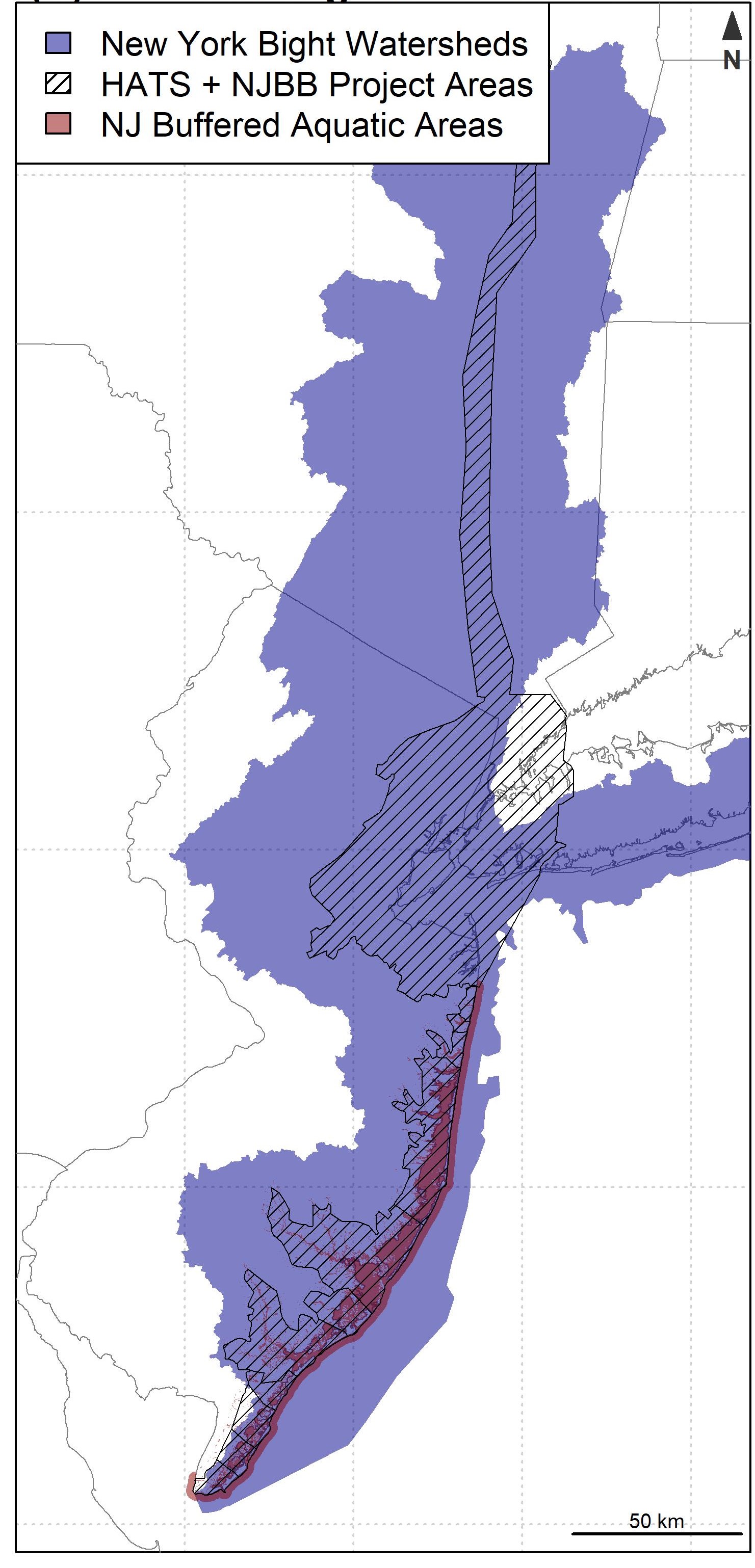

The cumulative project area of the ongoing CSRM studies exceeds 3,000 mi2 and covers multiple states. The spatial extent of model application was defined by a sequence of three sequentially smaller filters (Figure 2):

New York Bight: The USFWS defined the ecosystems of the New York Bight in 1997 as the “open ocean region south of Long Island and east of New Jersey, known as the New York Bight proper” and all associated upstream estuaries, waters, and lands. This large spatial domain covers 31,276 mi2 (10,206 mi2 upland watershed and 21,070 mi2 estuarine or marine). Specifically, the watershed is defined by ten 8-digit Hydrologic Unit Code (HUC) watersheds (02020006, 02020007, 02020008, 02030101, 02030103, 02030104, 02030105, 02030202, 02040301, and 02040302). The USFWS Bight definition includes all marine ecosystems offshore. However, given the nearshore scope of USACE’s studies, seaward extent is limited to ecosystems above a 20m depth contour (i.e., the USFWS definition of “nearshore”)((USFWS) 1997). This watershed boundary and seaward limit have a total area of 13,420 mi2((USFWS) 1997).

Project Boundaries: The Bight ecosystem includes many upland and coastal ecosystems beyond the project boundaries (e.g., Eastern Long Island). The USACE study boundaries provide a second filter on the spatial limits of the NYBEM. The New York Bight ecosystem contained within the project boundaries has an area of 2,930 mi2.

Aquatic Ecosystems: A key focus of the NYBEM is assessment of indirect effects of proposed actions. Currently, upland and shoreline ecosystems above mean higher high water (MHHW) are not included in the models. Impact assessments from these systems (e.g., dunes, scrub-shrub, riparian zones) are better understood from prior impact analyses. Additionally, these systems are likely to experience fewer indirect impacts, and methods are generally available for assessing direct impacts. Upland ecosystems are not explicitly removed from the spatial domain at this phase, but are removed below through the absence of any patch-scale models at elevations above MHHW and the absence of hydrodynamic data in uplands.

Figure 2.1: NYBEM model domain: (left) Components of model domain, (right) NYBEM domain.

2.2 Phased Approach

USACE planning studies sequentially make decisions about potential actions and buy-down risk and uncertainty to inform the next level of decision, before narrowing in on a recommended alternative. Furthermore, the USACE studies have proposed a “tiered” NEPA assessment, which is designed to gather more data and refine outcomes as a project proceeds. The NYBEM toolkit must be capable of responding to evolving project planning needs and data availability as these studies develop. As such, model development is explicitly being conducted in “phases,” and NYBEM tools and methods will evolve alongside project planning. In each phase, development will proceed iteratively through the cycle described above of conceptualization, quantification, evaluation, application, and communication. Table 2.1 presents key aspects of this phased approach to development.

| District Planning Milestone | Interim Report | Draft Feasibility Report | Final Feasibility Report |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Decision | Preliminary Screening | Alternatives Analysis | Design and Operation of Recommended Alternative |

| Scope of Environmental Effects | Direct | Direct + Indirect | Direct + Indirect + Cumulative |

| Spatial Extent of Environmental Effects | Project footprint | Offsite hydrodynamic change | Mitigation requirements |

| Anticipated Outputs | Project footprint | Habitat Quantity and Quality (by type) | Habitat Quantity, Quality, and Connectivity (by type) |

| Analytical Effort | Rapid Screening | Moderate | Detailed |

| Hydraulic Forcing | Existing Condition | One year of tidal forcing + Two sea levels | Multiple years of tidal forcing + Multiple sea levels |

| Model Inputs | Footprint | Footprint + Tidal Range + Salinity + Hydrodynamics + Env Data | Footprint + Tidal Range + Salinity + Hydrodynamics + Env Data + Sediment + Temperature + Waves + Water Quality + Other |

2.3 Mediated Modeling

The NYBEM intends to assess ecological consequences of alternative infrastructure options in a large, diverse ecosystem with many stakeholders and perspectives. “Mediated modeling” is used here to describe the family of techniques for building consensus among multiple partners to produce credible and defensible ecological models in a transparent way (Belt et al. 2006). There are many types of stakeholder-based model development processes that overlap in approach and emphasize collaboration: Model Prototyping, Participatory Modeling, Group Model Building, Companion Modeling and Mediated Model Development (See reviews by Voinov and Bousquet 2010; Gray et al. 2017; and Hall, Lazarus, and Thompson 2019). These processes are generally well-suited to environmental management problems that are politically and publicly-sensitive, complex, and engage diverse audiences (Belt et al. 2006).

For NYBEM, a suite of workshop-based model development methods are adapted from Herman et al. (2019). These workshops utilize a lecture-exercise format, where participants are led through the theory of a particular aspect of modeling (e.g., conceptual modeling) and then apply said theory to a focal ecosystem (i.e., the New York Bight). The workshops structure the iterative development of NYBEM with subsequent research and synthesis between meetings (See McKay et al. 2021 for additional detail). Appendix B summarizes workshop logistics and focal topics. Key milestones in model development are briefly described below, but the overarching strategy is to engage larger audiences and more formal forms of model evaluation as the toolkit develops.

Preliminary workshop with Philadelphia District (January 2019): A preliminary conceptual model was developed with USACE Philadelphia District team members, which focused generally on issues potentially relevant for environment compliance at the broadest level.

USACE workshop with Philadelphia and New York Districts (March 2019): A joint team from multiple USACE Districts was convened, and a strategy was proposed to develop NYBEM around key ecosystem types to reduce the dimensionality and complexity of the modeling problem and structure the path forward for model development.

Interagency conceptual modeling workshop (June 2019): Fifty scientists and environmental managers (from federal, state, and local government as well as select non-profit organizations and academic units) were brought together to focus on the development of conceptual models supporting the NYBEM. This workshop utilized a series of posters and activities for attendees to provide input on relevant variables and processes for each ecosystem type.

Interagency numerical modeling workshop (November 2019): A subset of attendees (20+) from the June 2019 workshop reconvened to discuss findings from the prior workshops. Prior to this meeting, the posters from June were formalized and synthesized with available scientific literature. At this meeting, attendees were able to review and revise preliminary versions of the model structure.

Phase-1 model documentation (April 2022; this report): This report provides model development status as applied to the Draft Feasibility Report and Environmental Impact Statement for each study. USACE requires assessment and external evaluation of ecological models used in Feasibility-level planning decisions (i.e., model certification), and this report will be peer-reviewed according to these agency procedures.

Phase-2 development (Fall 2022 / Winter 2023): Habitat quality and system connectivity tools will be further developed following the release of the Draft Feasibility Reports. Any modifications of models will also undergo review and certification.

Rapid timelines and iterative development also encourage a transparent approach for model documentation. We adopt a growing family of methods for “reproducible research,” which embrace code and data sharing, enable review processes, and facilitate use of methods and results. Specifically, R Markdown is applied to development and document models, which are coded in the R Statistical Software. These tools minimize data transfer errors and facilitate internal inspection of code as it is developed. Similarly, all model code is contained within a transportable R-package (i.e., nybem) following common development procedures.